Fieldwork report by Environmental Studies PhD candidate and Glacier Lab member Zac Provant.

When I arrived in Juneau on March 11th, 2022, winter disasters were on people’s minds. In December 2020, Haines, Alaska experienced a deadly landslide that destroyed houses and killed two people. In February 2021, neighborhoods in downtown Juneau were evacuated due to extreme risk of historic avalanches. On March 24th, 2022—while I was in Juneau studying avalanches—Anchorage was hit by a massive avalanche that left debris as deep as 80 feet between houses and across roads.

This ongoing attention to winter hazards in Alaska reflects a longstanding awareness that Alaskan mountain ranges are dangerous places to live. In Juneau, people have a particularly infamous relationship with avalanches and landslides. For decades, news reporters and scientists have spread stories of disaster: National Geographic Magazine called Juneau “the nation’s worst risk for an avalanche disaster”, and in the 1950’s avalanche science legend Ed LaChapelle kicked off the decadal cycle of experts recommending no more development in certain parts of downtown Juneau. As Tom Mattice—Juneau’s Emergency Operations Manager—described in an interview with local news, avalanche scientists visiting Juneau all say the same thing: “we can’t believe you built here.”

Image 1. A natural avalanche barreling down the Behrends avalanche path. These slides occur every year, often coming within 100 meters of houses. An avalanche large enough to damage houses has not occurred since 1962. Image from the City and Borough of Juneau.

As visualized in the image above, Juneau’s concern for avalanche and landslide risk is not simply a detached fear of potential destruction based on expert opinions, avalanche forecasts, or over-protective regulations. There have been hundreds of dangerous avalanches in Juneau since it was developed as Alaska’s first mining town in the late 19th century. A document buried in a City and Borough of Juneau (CBJ) file cabinet lists many of these events, with the first recorded avalanche wiping out 3 cabins in 1887 and the well-known 1962 avalanche on the Behrends path destroying “numerous buildings, vehicles, and trees.” Many currents residents also have a clear memory of the 2008 avalanche that destroyed Alaska Electric Light and Power facilities and caused an energy crisis lasting nearly six months. A resident of a downtown hazard zone told me she paid over $3000 for electricity alone over that six-month period—a cost her family really couldn’t afford. This same woman had to evacuate her home in 2021, and she showed me her own recent cellphone video of an avalanche flying down the mountain to fully cover Thane Road. To her—and to everyone I spoke with in Juneau—deadly avalanches and landslides aren’t an abstract, back-of-mind risk like the Cascadia earthquake or the Yellowstone eruption. These winter hazards are a part of Juneau’s history, and this history plays an important role in residents’ everyday experiences.

In response to this long history of environmental disaster, local news stations, city officials, and avalanche experts have worked through various options for hazard mitigation in Juneau. This includes special avalanche and landslide property insurance, development and zoning regulations, avalanche forecasting, engineering projects, and home buyouts. The CBJ engages all of these mitigation options except home buyouts, which Tom Mattice tells me won’t realistically happen until another massive avalanche ends in tragedy. Residents in high hazard zones like the Behrends neighborhood and White subdivision have additional forms of insurance, the CBJ has regulations for property development in hazard zones, organizations like the Department of Transportation and Alaska Electric Light and Power employ their own private avalanche forecasters, and engineering projects are repeatedly proposed and constructed to protect public and private property.

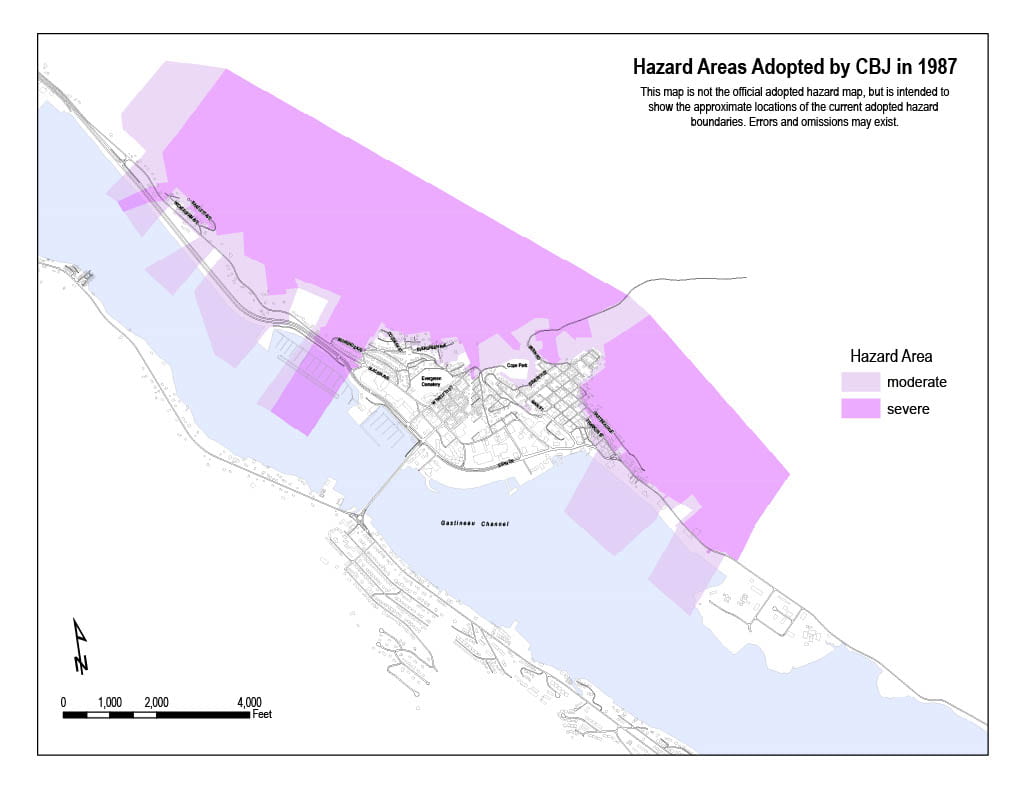

Image 2. This current official avalanche and landslide hazard map was adopted in 1987 and is based on science from the 1970’s. There have been multiple attempts to update the downtown hazard maps, but these newer maps have not been adopted due to concerns about increased development regulations, property values, and insurance premiums. Image from the City and Borough of Juneau.

Image 3. Mike, Alaska Electric Light & Power’s avalanche forecaster, digs a pit to check snow stability on a steep slope near the Snettisham Dam. There are powerline towers at risk of being destroyed by an avalanche, so AEL&P regularly tests snow stability during dangerous conditions and conducts avalanche mitigation if necessary (often using a helicopter and daisy bell). Image from Zac Provant.

Yet when people talk about hazards and hazard mitigation in Juneau, they often fail to contextualize how people actually experience avalanches and landslides as a part of their daily lives. Of course, people don’t experience hazards universally—a fact that is clearly demonstrated by the high risk of a deadly avalanche or landslide in multiple downtown zones and the impossibility of a slide a few miles away in the Mendenhall Valley. However, it is not just exposure to hazards that influences someone’s vulnerability. There are also significant differences in how people experience the impacts of avalanche and landslide risk, such as accessing insurance, navigating development regulations, comprehending hazard maps and avalanche forecasts, and absorbing the cost of damages or property value changes. An illuminating example of this can be found in Rebecca Elliot’s paper “Scarier than another storm“, which looks at how people experience NFIP flood rate insurance maps. In order to understand how the many forms of hazard mitigation will or won’t help keep people safe in Juneau, I believe that it is important to examine the often-overlooked impacts of hazard risk in people’s everyday lives.

Guided by scholarship in unnatural disasters and environmental justice, I see hazard vulnerability as being produced within a system rather than as a preexisting condition for marginalized people (see: Marino & Faas, 2020). My research therefore unpacks how actors and institutions in Juneau influence the way hazard vulnerability materializes within the city. Do the mitigation strategies for avalanche and landslide risk help some people while disadvantaging others? Do wealthier residents have different experiences with hazard risk given their access to engineering consultants, insurance options, and political power? How are the avalanche experts, local officials, and residents addressing climate change as a component of hazard risk and vulnerability?

My research trip to Juneau in March 2022 jumpstarted an exciting new stage for my dissertation fieldwork and data analysis. I left with a solid foundation of key research themes and thought-provoking stories. I conducted 17 informal interviews with residents, city officials, non-profit directors, and avalanche experts, and I collected hundreds of pages of unpublished documents on the history of avalanche and landslide management in Juneau. My next steps include remote interviews, document analysis, and of course more time in Juneau. I will continue to examine how people in hazard zones influence, are erased from, and are impacted by hazard mitigation stories and strategies. As climate hazards become more frequent and more severe—from hurricanes to heat waves to avalanches—I offer the overlapping projects of hazard mitigation and climate adaptation a new approach that helps contextualize how vulnerability is actually experienced in a local community.