Mark Carey joined the rest of his multidisciplinary Navigating the New Arctic (NNA) research team for ice-ocean-society research in east Greenland during August 2023. Their project, funded by the National Science Foundation’s NNA program, is called “Global changes, local impacts: Study of glacial fjords, ecosystems and communities in Greenland.” A recent article in Oceanography gives an overview of the project that runs through 2026, while the August 2023 NNA Newsletter explains the research activities.

This summer was the first time they jointly conducted fieldwork together. Being on the ship together for more than two weeks solidified the group and inspired many conversations about collaboration, interdisciplinary research, and connections with communities and Greenlandic partners.

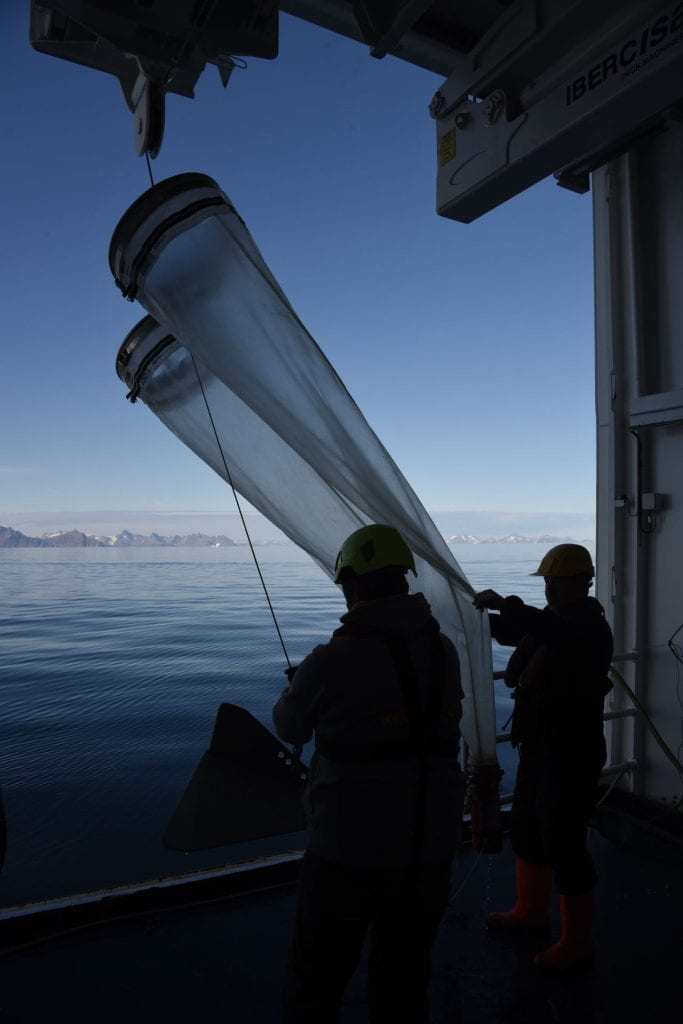

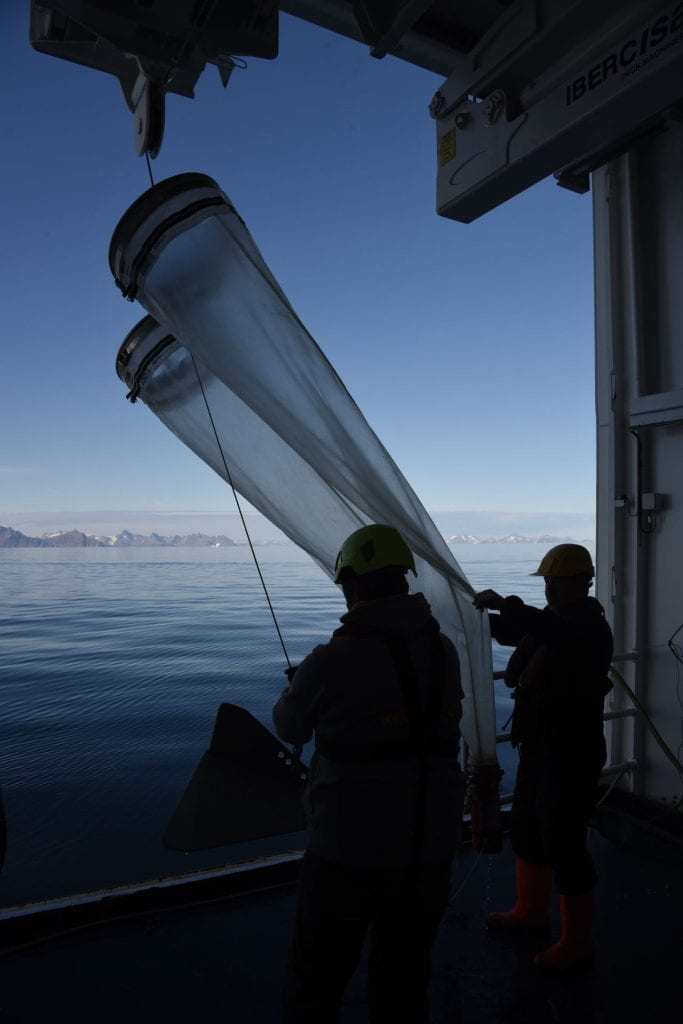

They set sail in early August from Reykjavik, Iceland, on the RV Tarajoq, an oceanographic and fisheries research vessel owned and operated by the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources. Their goal: study the Sermilik fjord system and the continental shelf ocean through multidisciplinary approaches that involved collaboration across the team of physical and biological oceanographers, fisheries biologists, glaciologists, climate modelers, and social scientists.

A principal goal of the cruise was scientific research to understand fjord dynamics, circulation, and human dimensions. For the last decade or so, scientists have come understand the way warm ocean water enters the fjords and melts the glacier outlets of the Greenland Ice Sheet. But fjord circulation is complex, and the team strives to understand life in the fjord as well as the physical system. This requires many disciplinary approaches. It also involved communication with and input from communities along the fjord, especially a schoolteacher from Tiilerilaaq.

Another key objective was collaboration and building relationships through shared field research experiences. Carey has recently argued that multidisciplinary teams can thrive and improve research when they spend time together in the field, learn each other’s research methods, and share unstructured and informal times together that often spark some excellent collaborative ideas (see Alagona, Carey, and Howkins, 2023). On this Greenland cruise, Carey worked the noon to midnight shift on the ship, assisting with oceanographic data collection and learning new fields and research practices. The teamwork and shared experiences—and new friendships—has laid an ideal foundation for continued collaboration and fresh insights into the ice-ocean-society dynamics of the fjord system.

Carey will continue work on this project back at the UO, working closely with undergraduate Glacier Lab members Mira Cross and Olivia Black. They are focusing on fisheries policy and management, public perceptions of Greenland fjords, and the human drivers of change within fjords. Carey is working to build relationships with Greenlandic scholars and communities as well. After all, Greenland priorities and plans must ultimately shape the research. Next steps will thus involve on-the-ground learning in Greenland and from Greenlanders, with the goal of further expanding collaboration beyond the terrific current partners at the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources.